“โกโบริ” คือคนทรยศชาติในสายตา “ชาวญี่ปุ่น” ?

นวนิยายอมตะ และภาพยนตร์เรื่อง “คู่กรรม” ว่าด้วยเรื่องราวของโกโบริ และอังศุมาลิน ทำให้คนไทยรู้สึกดีต่อคนญี่ปุ่น แต่หากมองในระบบหนี้บุญคุณในสังคมญี่ปุ่นแล้ว คนญี่ปุ่นส่วนหนึ่งจะมองว่า โกโบริ เป็นคนทรยศชาติจากที่พฤติกรรมของโกโบริ ขัดกับระบบความเชื่อเกี่ยวกับพันธะหน้าที่ต่อประเทศชาติ

ก่อนจะอธิบายถึงเรื่องโกโบริ คงต้องพูดถึงลักษณะคติทางสังคมญี่ปุ่นด้วย สังคมญี่ปุ่นขึ้นชื่อเรื่องระเบียบวินัย และความรักชาติมาตั้งแต่อดีต สิ่งที่ยึดเหนี่ยวสังคมญี่ปุ่นให้ยังคงรักษาความกลมเกลียวและคติให้ความสำคัญกับกลุ่มมากกว่าปัจเจกนี้ คือ พันธะหน้าที่ซึ่งสังคมกำหนดให้สมาชิกต้องประพฤติตามในด้านต่างๆ อาทิ ตระกูล ครอบครัว และประเทศ ซึ่งความคิดเห็นของยุพา คลังสุวรรณ นักวิชาการที่ศึกษาเรื่องสังคมญี่ปุ่นและรวบรวมในหนังสือ “ญี่ปุ่นสร้างชาติด้วยความรักและภักดี” มองว่าพันธะหน้าที่ต่างๆ ที่คนญี่ปุ่นต้องประพฤติปฏิบัตินั้นมีมากมายและย่อมมีขึ้นเพื่อสร้างความสงบเรียบร้อยอันนำไปสู่ความกลมเกลียวกันนั่นเอง

ยุพา คลังสุวรรณ อธิบายว่า ด้วยลักษณะทางสังคมญี่ปุ่นที่เป็นสังคมแบ่งลำดับชั้น คนในลำดับชั้นต่างๆ ก็มีพันธะหน้าที่ของตัวเองตามที่สังคมญี่ปุ่นกำหนดกฎเกณฑ์ต่างๆ ให้สมาชิกปฏิบัติ สำหรับผู้ที่ละเลยนอกลู่นอกทางก็จะถูกตัดสินว่าอยู่ผิดที่ผิดทาง

รูปแบบพฤติกรรมที่สังคมญี่ปุ่นกำหนดขึ้นก็มีสำหรับทุกกลุ่ม ไม่ว่าจะเป็นเพศไหน ชนชั้นใด อายุเท่าไหร่ และประกอบอาชีพอะไร ตราบใดที่ยังเป็นสมาชิกในสังคมญี่ปุ่นก็ต้องปฏิบัติตามรูปแบบพฤติกรรมที่กำหนด

ที่มาของพันธะและรูปแบบพฤติกรรมทางสังคมนี้อาจสืบความย้อนกลับไปถึงอิทธิพลจากสังคมชุมชนในอดีตที่ต้องอยู่ร่วมกัน ช่วยกันเพาะปลูก และป้องกันภัยจากภายนอก การช่วยเหลือเกื้อกูลกันส่งผลให้สมาชิกมีพันธะผูกพันและช่วยเหลือซึ่งกันและกัน ชุมชนหรือครอบครัวขนาดย่อมที่มีอยู่เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของครอบครัวใหญ่ (ประเทศ) ซึ่งสังคมญี่ปุ่นได้กำหนดพันธะหน้าที่ผูกพันเพื่อให้ทุกคนอยู่ร่วมกันอย่างราบรื่น อาทิ อน กิริ นินโจ

นินโจ (Ninjo) คือ อารมณ์ความรู้สึกของปัจเจกที่มีต่อผู้อื่นซึ่งเกิดขึ้นเองโดยธรรมชาติ เช่น ความรัก ความเศร้า ความสงสาร ความเห็นอกเห็นใจกัน ฯลฯ หรืออาจกล่าวได้ว่าเป็น “มนุษยธรรม” เป็นความรู้สึกจากใจ จะมีความสัมพันธ์หรือไม่มีความสัมพันธ์กันมาก่อนก็ได้ เป็นเชิงจิตวิทยาส่วนบุคคล โดยที่ “นินโจ” สำหรับสังคมญี่ปุ่นก็มีกรอบความเหมาะสมกำหนดอยู่เช่นกัน

ขณะที่ กิริ (Giri) เป็นพันธะทางสังคมซึ่งทำให้สมาชิกในสังคมต้องปฏิบัติตามเกณฑ์ที่สังคมคาดหวังเพื่อให้ถูกรับรู้ว่าเป็นผู้ทำหน้าที่ได้สมบูรณ์ กล่าวได้ว่าเป็นแรงผลักดันทางศีลธรรม (Moral Force) ยุพา อธิบายเพิ่มเติมว่า กิริเป็นแนวคิดที่เกี่ยวกับพันธะทางสังคมซึ่งจัดตั้งขึ้นในสมัยศักดินา เช่น ซามูไรต้องรับใช้เจ้านายด้วยชีวิต หรือใช้ชีวิตของตัวเองเพื่อตอบแทนเจ้านาย การตอบแทนบุญคุณเป็นคุณค่าสูงสุดทางศีลธรรม และควรค่าแก่การปฏิบัติ

กิริยังเป็นพันธะความสัมพันธ์ที่ทำให้เกิดการพึ่งพากันจนทำให้เกิดหนี้บุญคุณ หรือที่สังคมญี่ปุ่นเรียกกันว่า “อน” (on) ต่อไป สังคมญี่ปุ่นในปัจจุบันใช้กิริถูกนำมาใช้ในการรักษาสถาบันทางสังคมให้ดำเนินอย่างราบรื่นแม้ว่าทั้งกิริและนินโจไม่ได้ถูกบันทึกเป็นลายลักษณ์อักษรก็ตาม

กิริและนินโจมีบทบาทมากในสังคมสมัยศักดินา พันธะทางความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างเจ้านายและลูกน้อง ทั้งสองฝ่ายต่างมีกิริและนินโจต่อกัน เจ้านายปกครองและเลี้ยงดูลูกน้องให้มีความเป็นอยู่ที่ดี ขณะที่ลูกน้องก็ซื่อสัตย์และภักดีต่อเจ้านาย

สิ่งที่น่าสนใจคือ “อน” หมายถึง ภาระที่ต้องทำเพื่อตอบแทนผู้ให้ความช่วยเหลือ เป็นทั้งหนี้ทางสังคมและหนี้ทางใจ อันเป็นค่านิยมซึ่งทำให้ญี่ปุ่นรักษาความเป็นระเบียบได้ อน เกิดขึ้นเมื่อได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากผู้อื่นหรือได้รับสิ่งของจากผู้อื่น และเป็นหนี้ซึ่งผู้รับเองรับมาทั้งโดยตั้งใจ ไม่ตั้งใจ และเป็นหนี้ที่เกิดขึ้นโดยธรรมชาติ เช่น ลูกต้องกตัญญูต่อพ่อแม่ซึ่งเป็นผู้ให้ชีวิต

อน ทำให้ซามูไรที่ได้รับที่ดินและได้รับคุ้มครองจากเจ้านายต้องรับใช้เจ้านายเท่าชีวิต หรือนักเรียนก็เป็นหนี้บุญคุณผู้สอน หรือการช่วยเหลือแบบที่เกิดขึ้นเฉพาะหน้าดังเช่นนิทานเรื่องโชกุน

นิทานโชกุน เรื่องมีอยู่ว่า โชกุนมีคนรับใช้และลูกคนรับใช้ที่อาศัยในปราสาท เมื่อเรือที่โชกุนโดยสารล่ม ลูกคนรับใช้ในปราสาทช่วยชีวิตโชกุนไว้

โชกุน มี “อน” ต่อลูกคนรับใช้ที่เป็นผู้ช่วยชีวิต และต้องตอบแทนบุญคุณลูกคนรับใช้นี้ไปชั่วชีวิตโดยไม่พิจารณาถึงสถานภาพ

บุญคุณประเภทนี้มีทั้งเกิดภายหลัง และติดตัวมาแต่กำเนิด อาทิ บุญคุณต่อองค์จักรพรรดิ “เท็นโนะ โนะ อน” (Tenno no on) หรือบุญคุณต่อประเทศ “คุนิ โนะ อน” (Kuni no on) ซึ่งถือเป็นหนี้ระดับสูงที่สุดและติดมากับชาวญี่ปุ่น เป็นหนี้ที่ต้องเสียสละต่อจักรพรรดิโดยไม่มีขอบเขต ทหารญี่ปุ่นรับรู้ว่าบุหรี่ทุกมวน และเหล้าที่ดื่ม คือการเพิ่มหนี้บุญคุณที่มีต่อจักรพรรดิ (แม้ญี่ปุ่นรับวัฒนธรรมจีนมา แต่ไม่ได้รับจริยธรรมเรื่องผู้ปกครองจีนที่ว่า ถ้าผู้ปกครองไม่ดี สวรรค์จะส่งคนดีมาปราบและขึ้นปกครองแทน)

หนี้บุญคุณสำหรับญี่ปุ่นอย่าง อน เป็นหนี้ที่มีภาระผูกพัน เมื่อเกิดแล้วต้องตอบแทน การไม่ตอบแทนบุญคุณเหมือนทำผิดบรรทัดฐานทางสังคม แต่ความเข้มข้นของบุญคุณก็เปลี่ยนแปลงไปตามสมัยด้วยเช่นกัน

บุญคุณที่ว่ามาข้างต้นเป็นบุญคุณในช่วงก่อนสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 เมื่อเข้าสู่ช่วงสงคราม และหลังสงคราม ยุพา อธิบายว่า ความเข้มข้นของบุญคุณก็แตกต่างกันออกไป

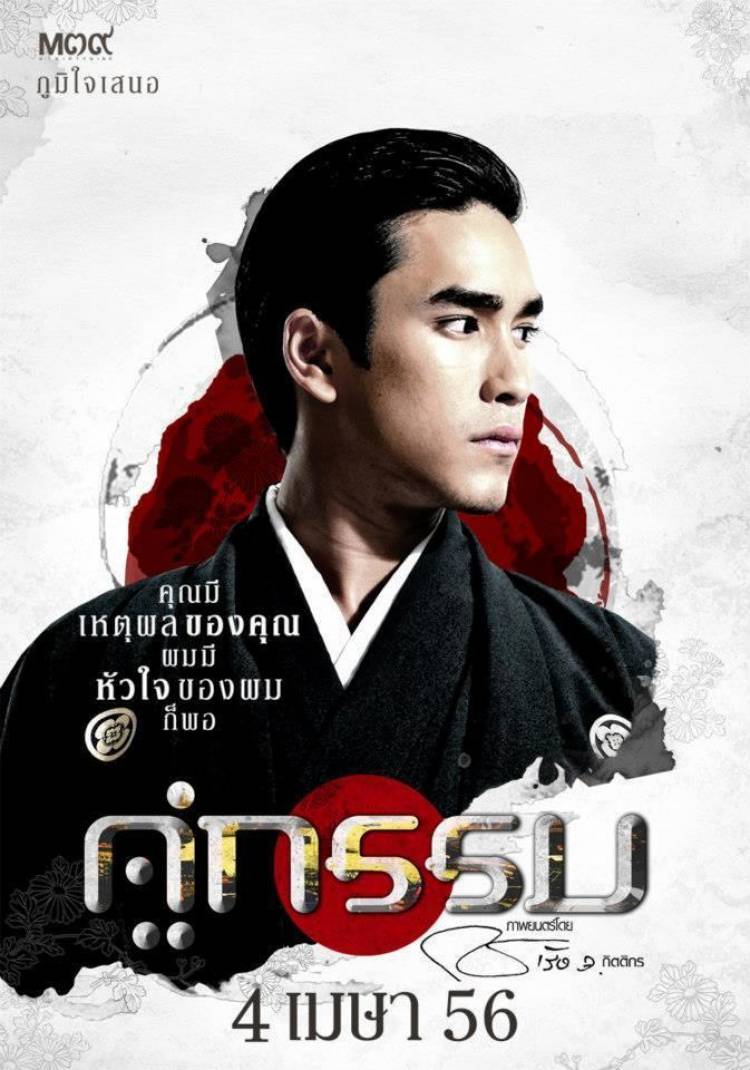

ตัวอย่างที่ถูกหยิบยกมาพูดถึงคือ เรื่อง “โกโบริ” ตัวละครในนวนิยายอมตะซึ่งเป็นทหารญี่ปุ่นที่มาประจำการในประเทศไทยที่บางกอกน้อย โกโบริที่หลงรักอังศุมาลิน ปล่อยแฟนเก่าของอังศุมาลินให้หนีไป ผู้ชมชาวไทยก็นิยมชมชอบโกโบริในเรื่องคู่กรรมมาก แม้จะเป็นเรื่องผิดกฎก็ตาม

ความคิดเห็นของยุพา ผู้เขียนหนังสือ “ญี่ปุ่นสร้างชาติด้วยความรักและภักดี” มองว่า ผู้เขียนไม่ได้เขียนตัวละครให้เป็นคนที่มีอุปนิสัยแบบญี่ปุ่น แต่มาสอดแทรกในยุคที่มีผู้ผลิตภาพยนตร์ โดยผู้ผลิตสร้างบรรยากาศ สอดแทรกวัฒนธรรมญี่ปุ่นอันเป็นการเพิ่มรายละเอียดเพื่อดึงดูดผู้ชม ภาพยนตร์เรื่องคู่กรรมไม่อาจสะท้อนความเป็นญี่ปุ่นได้ และเป็นเรื่องที่คนญี่ปุ่นรู้สึก แต่ในอีกด้านหนึ่ง คนญี่ปุ่นก็รู้สึกดีกับคู่กรรม เพราะเป็นเรื่องที่สร้างภาพลักษณ์เชิงบวก แตกต่างจากภาพเดิมที่เป็นเชิงลบซึ่งผู้คนอาจติดภาพจำว่าญี่ปุ่นเป็นสัตว์เศรษฐกิจและทหารที่โหดร้าย กระทั่งให้เงินอุดหนุนการวิจัยแก่ชาวไทยเพื่อศึกษาเรื่องคู่กรรม

ยุพา เล่าว่า รองศาสตราจารย์ไว จามรมาน เคยถามคนญี่ปุ่นว่ารู้สึกอย่างไรกับโกโบริ และอังศุมาลิน คำตอบที่นักวิชาการได้คือ โกโบริเป็นคนทรยศต่อชาติ และใช้คำว่า “อุระกิริ” (uragiri) ซึ่งหมายความว่า แทงข้างหลัง

รศ.ไว อธิบายว่า “อุระกิริ” เป็นคำที่ใช้โดยทั่วไปสำหรับคนไม่ดีที่เป็นคนภายนอก เมื่อใช้กับโกโบริ นั่นอาจสะท้อนว่า คนญี่ปุ่นมองโกโบริ เป็นคนทรยศที่ไม่ได้อยู่ภายในกลุ่ม เชื่อว่า ญี่ปุ่นโดยทั่วไปถือว่าโกโบริไม่ทำตามพันธะหน้าที่ ไม่มีความจงรักภักดีต่อประเทศ แต่ญี่ปุ่นไม่เคยวิจารณ์เรื่องนี้ออกสื่ออย่างแน่นอน ขณะที่ภาพโกโบริในเรื่องคู่กรรมสร้างภาพเชิงบวกให้คนญี่ปุ่น

อย่างไรก็ตาม หลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 สังคมญี่ปุ่นเปลี่ยนแปลงไปอย่างมาก สถานภาพขององค์จักรพรรดิลดลงมา สังคมญี่ปุ่นเปลี่ยนจากสังคมเกษตรเป็นสังคมอุตสาหกรรม ชาวนาเข้ามาทำงานในเมือง โครงสร้างทางสังคมญี่ปุ่นก็เปลี่ยนแปลงไปด้วย ลักษณะการบริหารงานในองค์กร หรือครอบครัว แนวคิดเรื่อง อน กิริ นินโจ ก็เป็นสิ่งที่เริ่มเปลี่ยนแปลงไปด้วย แนวคิดเรื่อง “อน” ยังมีอยู่ในกลุ่มยากูซ่า แต่ก็ไม่เข้มข้นเหมือนช่วงก่อนสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2

หากจะศึกษาเรื่องความเปลี่ยนแปลงในระบบหนี้บุญคุณทางสังคม อาจต้องศึกษาค้นคว้าอย่างเจาะลึกกันต่อไป

(English)

Is "Kobori" a traitorous person in the eyes of "Japanese"? The novel and film "Kugumaru" about the story of Kobori and Angsumalin make Thais feel good about Japanese people. However, if viewed in the context of debt of gratitude in Japanese society, some Japanese people may see Kobori as a traitor due to his behavior conflicting with the belief system regarding national duty.

Yupa Klansuwann explains that due to the hierarchical nature of Japanese society, individuals in various social strata have their own responsibilities as prescribed by the different criteria and guidelines set forth by Japanese society. Those who deviate from the established norms and paths are judged to be in the wrong.

The behavioral patterns dictated by Japanese society apply to all groups, regardless of gender, social class, age, or occupation. As long as one remains a member of Japanese society, they are expected to adhere to the prescribed behavioral patterns.

The origins of bonds and social behavior patterns in Japanese society may trace back to influences from past community societies where individuals had to coexist, cooperate, and protect themselves from external threats. Mutual assistance led to members having interdependent bonds and aiding each other. Small communities or families existing as part of a larger family (nation), which Japanese society has designated duties to ensure smooth coexistence, such as On, Giri, and Ninjo.

Ninjo (仁情) refers to the innate human emotions towards others, such as love, sadness, compassion, empathy, etc. or can be described as "humanity." It's a feeling from the heart, whether there is a relationship or not. It's a personal psychological aspect, where "Ninjo" for Japanese society also has appropriate frameworks.

Meanwhile, Giri (義理) is a social obligation that requires members of society to adhere to the standards expected by society to be recognized as fulfilling their duties. It can be described as a moral force. Yupa elaborates that Giri is an idea associated with social obligations established in the feudal era, such as samurai serving their lords with their lives or using their lives to repay their lords. Repaying favors is the highest moral value and should be valued in practice.

Giri also represents a relational obligation that creates mutual dependence resulting in indebtedness or what is referred to as "on" (恩) in Japanese society. Present-day Japanese society uses Giri to maintain social institutions running smoothly, even though both Giri and Ninjo are not explicitly recorded.

Both Giri and Ninjo played significant roles in feudal society. Relationship obligations between lords and vassals, where both sides have Giri and Ninjo towards each other. The lord governs and takes care of the vassals for their well-being, while the vassals are loyal and respectful to the lord.

What's interesting is "on," meaning the obligation to reciprocate help, is both a societal and emotional debt. It's both a social and emotional debt. On occurs when receiving help from others or receiving something from others and becomes a debt received intentionally, unintentionally, or naturally. For example, children must be respectful to their parents, who gave them life.

On leads to samurai who received land and protection from their lords to serve their lords for life. Or students being indebted to their teachers, or specific one-time help, as in the folklore of Shokun.

The folklore of Shokun tells that when Shokun's ship sank, the servants and his son in the castle saved Shokun's life.

Shokun has "on" towards the servant's son who saved his life and must repay this servant's kindness for the rest of his life without considering status.

This type of gratitude can be both acquired later in life and ingrained from birth. For example, gratitude towards the emperor "Tenno no on" or gratitude towards the country "Kuni no on," which are considered the highest level of debt and are deeply ingrained in Japanese people. It's a debt that must be paid to the emperor without limits. Japanese soldiers understand that every cigarette smoked and every sip of alcohol consumed is an increase in the debt of gratitude owed to the emperor. (While Japan adopted Chinese culture, they didn't adopt the Chinese ethical principle regarding parents, which says that if parents are not good, heaven will send good people to replace them.)

The debt of gratitude, "on," for Japan, is a binding obligation that must be repaid once incurred. Not repaying gratitude is akin to social misconduct. However, the intensity of gratitude also changes with time.

The above-mentioned gratitude refers to the pre-World War II era. As the war ensued and post-war, Yupa explains that the intensity of gratitude varied.

An example often cited is the character "Kobori" in the novel "Kugumaru," a Japanese soldier stationed in Thailand during the war. Kobori, who fell in love with Angsumalin, let go of Angsumalin's former lover. Thai audiences admired Kobori's character in the story despite his transgressions.

Yupa, the author of "Japan: Nation Building with Love and Gratitude," views that the author didn't portray characters with distinctly Japanese characteristics but rather inserted them into an era with film producers who crafted an atmosphere by integrating Japanese culture as added details to attract viewers. The film "Kugumaru" couldn't truly reflect the Japanese essence, which Japanese people feel. On one hand, Japanese people may feel good about the film as it presents a positive image, unlike the previous negative portrayals where Japan was depicted as an economic and military aggressor. This even led to funding research on relationships among Thai people.

Yupa recounts that Associate Professor Wai Chamrorn once asked Japanese people how they felt about Kobori and Angsumalin. The response from academics was that Kobori was a traitor to his nation, using the term "uragiri," meaning betrayal.

Assoc. Prof. Wai explains that "uragiri" is a term commonly used to describe someone who is morally corrupt and an outsider. When applied to Kobori, it might reflect how Japanese people perceive Kobori as an outsider, believing that he doesn't adhere to societal norms, lacks patriotism, and fails to fulfill his duties. However, Japan has never explicitly criticized this issue in the media. Meanwhile, the portrayal of Kobori in the film "Kugumaru" fosters a positive image among Japanese people.

Nevertheless, after World War II, Japanese society underwent significant changes. The status of the emperor diminished, transitioning from an agrarian to an industrial society, with farmers moving to urban areas. Consequently, Japan's social structure underwent transformations, affecting organizational management and family dynamics. Notions of "on," "giri," and "ninjo" also began to change, albeit not as intensely as before World War II.

To further understand these changes in the social system of gratitude, deeper investigation may be required.

![Boku Girl ch1 [ English ]](http://wutthakat.com/uploads/images/image_140x98_5c06cb06ee727.jpg)

![We Never Learn [ English ] Ch1 - part 2](http://wutthakat.com/uploads/images/image_140x98_5c06d909c0fea.jpg)

Facebook Comments (0)